Now that both houses of the German parliament have passed the new Digital Act (Digital-Gesetz, “DigiG”), the German healthcare system has certainty regarding the substance of the Act. The DigiG will be promulgated in the Federal Law Gazette within the next few days, and will have a major impact on the introduction and functionality of both the electronic patient record (elektronische Patientenakte, ePa) and the standardised e-prescription, on digital health applications (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen, DiGAs), and on the range of telemedicine services on offer.

In tandem with the Health Data Use Act (Gesundheitsdatennutzungsgesetz) (article of 13 February 2024, German only), passed at the same time, the DigiG is another milestone towards achieving the Federal Government’s goal of making Germany’s healthcare system more digital, more user-friendly and more efficient.

1. Obligatory e-prescription of pharmaceuticals in Germany

Electronic prescriptions (“e-prescriptions”, E-Rezepte) were introduced back in 2022. But their obligatory use across Germany failed until now on account of the e-prescription’s technical requirements and due to data protection concerns. The e-prescription is undergoing further development on the basis of the DigiG, and has been the binding standard in pharmaceutical supply since 1 January 2024.

How e-prescriptions work

Physicians issue an e-prescription digitally, signing it electronically with their health professional card. It is then stored and encrypted in the telematics infrastructure, where pharmacies can access it later. On the technical side, practices need an electronic health professional card, a link to the telematics infrastructure with a corresponding connector, and a practice management system that meets e-prescription requirements.

Patients receive an access code (known as an e-prescription token) that they then give the pharmacy for the prescription to be filled. Pharmacies are obliged to fill e-prescriptions. There are various technical ways of sending the token to the patients and of having the prescription filled by the pharmacy:

- The e-prescription app is available as a digital solution.

- The token can also be printed out on paper and given to the pharmacy as before.

- Since 1 July 2023 it has also been possible to have the e-prescription filled using the electronic health card, which needs to be inserted into a corresponding reader at the pharmacy.

- A new option became available on 1 January 2024: all private and statutory health insurance (SHI) funds may now include a function in their electronic patient record apps enabling e-prescriptions to be received and filled.

Integrating e-prescriptions into the electronic patient record

With regards to integrating e-prescriptions into the electronic patient record, the DigiG provides for more than merely showing an e-prescription on the app’s user interface. Unless the patient objects, further data will be sent to the electronic patient record, including the drugs dispensed, their batch number, and their dosage (“dispenser information”). So here as well, legislators have gone for an opt-out procedure that reverses the previous concept based on patient consent.

In future, data transfer will form one of the pillars of a digitally supported medication process. Together with further information on allergies, intolerances, pregnancies etc., the data will be made available to practices (unless the patient objects) and taken into account when prescribing drugs. For effective therapy, the interplay of e-prescription and electronic patient record promises added value in avoiding double prescriptions and improving drug safety, as physicians can better judge interactions with drugs already prescribed or with existing conditions. But that is not all. Germany’s healthcare telematics body, gematik, has been given new powers and taken on new tasks in shaping the e-prescription and developing the electronic patient record.

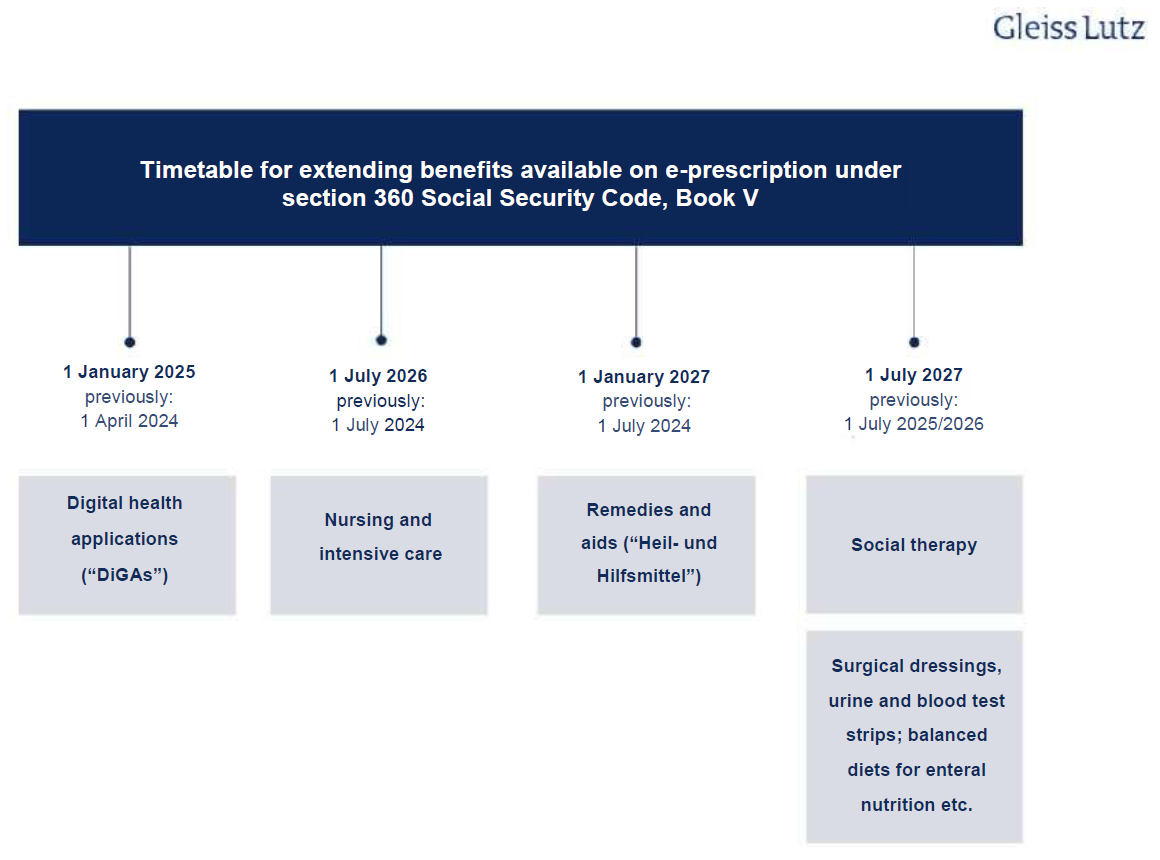

E-prescriptions have only covered prescription drugs to date

It is likely that e-prescriptions will cover all medicinal products in future. Currently, only prescription drugs fall under the scope of e-prescriptions, but this scope is to be gradually expanded. Section 360 Social Security Code, Book V (Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch, “SGB V”) is the main statutory provision on e-prescriptions and sets deadlines for this expansion. As the obligatory introduction of the e-prescription was delayed, however, the deadlines have been revised yet again and the DigiG amended in line with the new section 360 SGB V. The following overview shows the schedule for extending e-prescriptions to other benefits:

The e-prescription’s likely impact

E-prescriptions will simplify how prescriptions are issued, sent and filled in everyday practice. But online pharmacies and pharmacy platforms are also likely to benefit, as will logistics service providers that offer prompt delivery to patients directly on pharmacies’ behalf.

Thus far, e-prescriptions have played barely any practical role in this regard. For this reason, they have not yet made a tangible contribution to modernising the provision of pharmaceuticals in line with customer needs. These improvements in the use of telemedicine applications will further stimulate this industry, which is still in its infancy.

2. Digital health applications (DiGAs) and telemedicine

The DigiG will also significantly transform the regulatory requirements for “prescription apps”, and the following section discusses the most important planned changes for patients and digital health app developers. There are several regulatory improvements for telemedicine applications, too.

Digital health apps as an innovative component of standard care

The introduction of the Digital Healthcare Act (Digitale-Versorgungs-Gesetz, “DVG”) in 2019 laid the groundwork for the integration of digital health apps into standard care in Germany. An innovative industry of digital medical device manufacturers has since emerged, with 56 apps currently listed in the official digital health applications directory of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, “BfArM”). Six applications (provisionally) authorised as digital health apps have been removed from the list either at the request of the manufacturer or because no positive healthcare effect could be demonstrated.

The following provisions in the DigiG are aimed at increasing still further the role digital health apps will play in healthcare.

Digital health apps on par with other remedies and aids

Digital health apps are now treated the same way as other remedies and aids under the law, with patients now having a right to use these apps.

Availability for use within two working days

Aside from in a number of tightly restricted cases, SHI funds must ensure that digital health apps are available for use by patients within two working days of receipt of the prescription. There is no requirement for SHI approval, nor may SHI funds create de facto approval requirements, as such requirements would jeopardise prompt provision of care.

Digital health apps in higher risk classes

Under current legislation, only digital medical devices in risk class I (according to the classification rules of Annex VIII to the Medical Device Regulation (MDR)) may be prescribed as digital health apps. The DigiG extends statutory entitlement to such apps to include higher risk classes – specifically those in risk class IIb. In future, therefore, it will also be possible to use digital health applications in more complex therapeutic processes, for remote patient monitoring for example. This opens up completely new opportunities for digital health app developers.

Approval of digital health apps in such risk classes logically requires proof of direct medical benefit (“medizinischer Nutzen”) to the patient (such as an improvement in the state of health), and not just proof of a structural or procedural improvement in medical care that has a positive effect for the patient (“positiver Versorgungseffekt”).

“Companion apps” not covered

The DigiG does, however, limit the scope of what constitutes a digital health app: Approval will not be granted for apps that are used only to manage therapeutic products or are (permanently) linked to very specific medical aids or medicinal products.

Performance-based pricing to become mandatory

The way digital health apps are priced will change, with performance-based criteria playing a greater role. The DigiG stipulates, for example, that performance-based price components must comprise at least 20 percent of the remuneration amount. Transitional periods will apply to apps with an existing price agreement. Exactly how prices will be structured in future remains an open question.

DigiG no longer stipulates expiry of remuneration claim if patient declares non-use

The DigiG’s initial draft provided that a digital health app developer’s claim to remuneration would lapse if the patient indicated within 14 days of using the app for the first time that he/she would not use it on a permanent basis. This new provision, which would have caused considerable uncertainty for digital health app developers, was removed in the course of the legislative process after severe criticism.

Expansion of ban on referrals and agreements

The existing ban on referrals and agreements will be expanded. Developers of digital health apps will no longer be permitted to enter into legal transactions or agreements with medicinal product or medical aid manufacturers that are likely to restrict a patient’s freedom to choose specific products or aids. The Federal Government sees this as a way of preventing lock-in effects. It will therefore become unlawful to design digital health apps tailored to accompany treatment involving only one particular medicinal product or medical aid.

Technical equipment to become available on loan

In some cases digital health app developers will have to allow patients to borrow the technical equipment required to use their apps. By making it possible to borrow expensive accompanying hardware, the Federal Government hopes to reduce costs and increase sustainability. However, it is not yet clear in which cases this will apply.

Digital health apps during pregnancy

The aim is to treat digital health apps the same as any other remedies and aids offered to pregnant women and new mothers. This means that women will have the right to use relevant digital health apps both during and after pregnancy.

Patient authentication

Patients will be able to decide for themselves what level of authentication is required for access to a digital health app and may even opt for less stringent access requirements.

Monitoring digital health apps

The performance of all digital health apps listed in the directory must be assessed and the results reported to the BfArM on an ongoing basis. The results are also to be published in the directory from 1 January 2026 onwards. As already mentioned, part of a digital health app developer’s remuneration will in future depend on these results.

Breakout moment for telemedicine

In future, telemedicine apps will be part and parcel of healthcare, which is why the DigiG has lifted the previous restrictions on volumes. Once the German medical profession’s self-governing bodies have implemented the Act, SHI-accredited physicians will have greater flexibility and scope in offering video consultations.

Assisted telemedicine in pharmacies will also provide low-threshold access to healthcare, it is hoped. In addition, the DigiG enables telemedicine services to be performed by outpatient clinics linked to universities and psychiatric institutions as well as by psychotherapists as part of their consultation hours.

This will benefit both patients and telemedicine providers overall.