On 19 August 2020, Germany’s Federal Office of Administration (Bundesverwaltungsamt) updated its practice regarding the German Register of Ultimate Beneficial Owners (UBOs). The changes as to how UBOs are determined are significant, to say the least. Approval requirements, veto rights or blocking stakes that can prevent resolutions of the annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting are now treated as a means of control and basis for beneficial ownership on any level of shareholding. It’s a major shift in the basic principles for the determination of UBOs

Summary

On 19 August 2020, the Federal Office of Administration (Federal Office) updated its frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding the UBO Register under Germany’s Money Laundering Act (Geldwäschegesetz (GwG)). It contains major changes as to how UBOs are determined in single-level or multi-level shareholding structures.

On the level of the relevant entity, which is subject to notification obligations, any shareholder able to prevent a decision of the annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting is to be treated as a direct UBO. Where a unanimous resolution is required, every natural person with voting rights is an UBO, even if the shareholding is very minor. Beneficial ownership can even be derived from quora for adopting resolutions.

In a multi-level chain of shareholdings, there will be a shift in paradigm. For the natural person at the top of the chain to be an indirect UBO of an entity subject to notification obligations, – to date – a majority of shares or voting rights was required so that the shareholding in the entity could be attributed to him or her. In the Federal Office’s view, it now suffices that a natural person on the parent company level is able to prevent a decision of the annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting for this person to be an indirect UBO of the subordinate entity. A blocking stake against fundamental decisions such as amendments to the articles of association, capital measures or corporate transformations will be enough. If, for example, the articles of association stipulated that certain resolutions must be adopted unanimously, a single voting right would make a natural person an UBO and trigger the obligation to notify the UBO Register.

For a variety of reasons, we consider the new approach of the Federal Office to be incorrect under current law. This being said, all companies should check what impact the new FAQs could have on how “their” UBOs are determined. Legal risks that may exist can only be assessed in each individual case.

Direct UBOs

Pursuant to section 3(2) sentence 1 GwG, the UBO of an entity subject to notification obligations is any person who directly or indirectly holds more than 25% of the entity’s capital stock or voting rights or exercises control in a comparable manner.

The Federal Office had commented on veto rights in previous versions of the FAQs. If, by virtue of a veto right, a natural person had indirect or direct control over decisions of general assemblies, annual general meetings or shareholder meetings, this person was deemed an UBO under section 3(2) sentence 1 no. 3 GwG.

Under B.II.3 and B.II.4 in the most recent version of its FAQs, the Federal Office now states that this statement refers not only to explicit veto rights but also to statutory rules or provisions in articles of association that mandatorily require a shareholder to vote in favour of a resolution for it to be adopted. The Federal Office argues that if a shareholder can prevent a decision, e.g. because the articles of association require an unanimous resolution, this constitutes control in a comparable manner. In this case the threshold of 25% of shares or voting rights does not have to be exceeded for the shareholder to be an UBO. If the presence of a particular shareholding (e.g. 90%) is required for resolutions to be adopted at an annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting, this can also lead to beneficial ownership. However, if two or more shareholders would need to cooperate in order to prevent a decision by the entity, this would not make either of them UBOs.

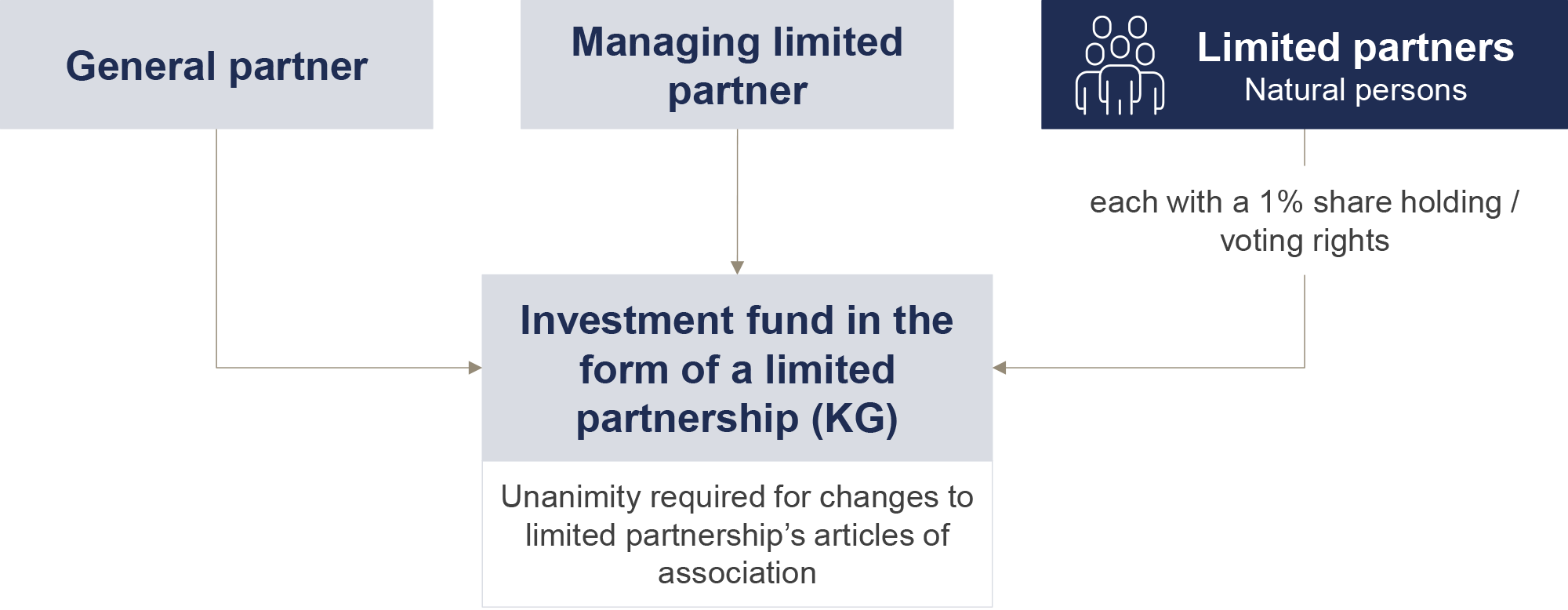

The example above shows an investment fund in the form of a widely held limited partnership (Kommanditgesellschaft, (KG)) where certain changes to the partnership agreement require unanimity. Here, every natural person participating in the limited partnership as a limited partner and able to prevent a change to the partnership agreement with his or her voting right would, in the Federal Office’s view, be an UBO of the limited partnership. Further potential UBOs would be the natural persons behind the general partner and the managing limited partner. In practice, this result would lead to almost unsolvable problems and would not correspond with what the legislator intended.

Indirect UBOs

With regard to multi-level shareholding structures, the prevailing legal view to date has been that a natural person must be able to exert a dominant influence (within the meaning of the German Commercial Code (Handelsgesetzbuch)) over the parent and intermediate companies in the chain for the shares or voting rights in the entity subject to notification obligations to be attributed to the natural person at the top of the chain. Therefore, in most cases and in the absence of other means of control, a majority of shares or voting rights was required for the natural person to become an indirect UBO of the entity subject to notification obligations. As a general rule, the simple fact that the natural person can block decisions was not sufficient for dominant influence.

According to the Federal Office’s new interpretation under B.III.2 to B.III.4 of the FAQs departing from this established view, a veto right against decisions of the annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting, or other “rights of prevention” equivalent to such veto rights (e.g. a blocking stake), will qualify as dominant influence. If a natural person can, directly or indirectly, prevent a decision of the annual general meeting or shareholders’ meeting at the “parent entity”, or a valid resolution is impossible without that person’s approval, such natural person is deemed to have dominant influence.

In the Federal Office’s view, this means that every holder of voting rights has a dominant influence if the articles of association provide for unanimity. Dominant influence is also given if the articles of association require a majority decision and the majority decision requires the consent of a single holder of voting rights. Also a blocking stake for fundamental resolutions of the annual general meeting or shareholders meeting (e.g. amendments to articles of association, capital measures, corporate transformations etc.) are deemed to constitute dominant influence.

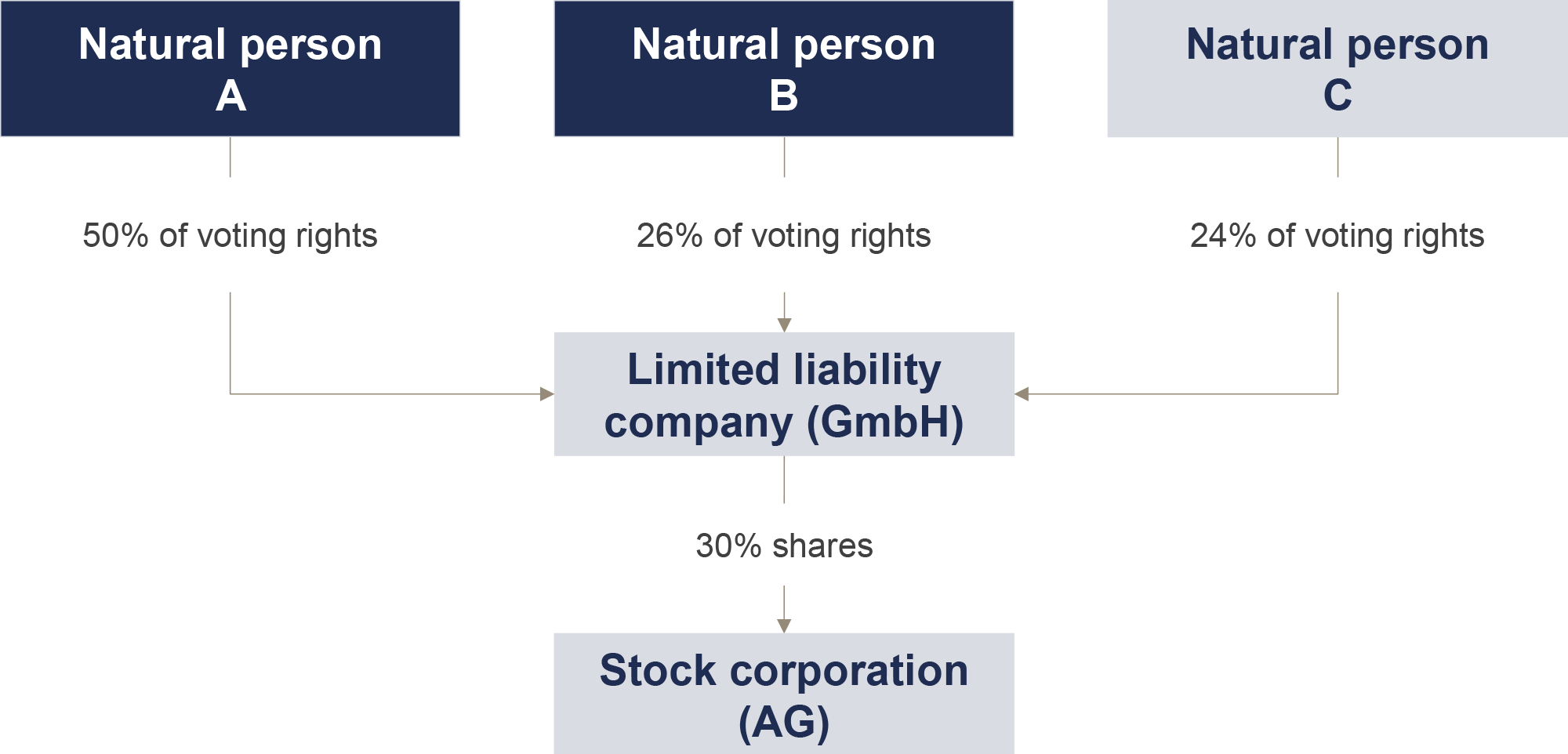

The example above shows a limited liability company (GmbH) and stock corporation (AG) with standard articles of association. Here, the Federal Office’s view is that natural persons A and B are the stock corporation’s UBOs; A because he or she is able to block majority resolutions in the limited liability company, and B because of the blocking stake against resolutions on fundamental issues. The limited liability company’s shares in the stock corporation are attributed to A and B owing to their respective “right of prevention”.

Should the articles of association stipulate a higher qualified majority for resolutions than a three-quarters majority, or even a unanimous resolution, even a shareholding of less than 25% may lead to an attribution of shares and to a qualification as indirect UBO.

Legal practitioners face a further difficulty: the precise scope of the “rights of prevention” required by the Federal Office for an attribution of shares and voting rights remains unclear in the FAQs. Do such rights need to cover “all” resolutions, resolutions on “fundamental issues”, several “decisions”, or only “one” decision? It is also unclear if, in the Federal Office’s view, in case of “rights of prevention”, the notification obligations can be deemed to have already been met through other publicly available documents and registrations exempting the relevant entity from having to notify the UBO Register of the UBO’s details.

Assessment and recommendation

The Federal Office’s new practice in determining UBOs – in particular in multi-level shareholding structures – would constitute a shift in paradigm. We consider it to be incompatible with various aspects of Germany’s Money Laundering Act and related provisions in the German Stock Corporation Act (Aktiengesetz), German Commercial Code and Securities Trading Act (Wertpapierhandelsgesetz), as well as an incorrect interpretation of current law.

The examples above illustrate very clearly what far-reaching consequences the Federal Office’s view would have. The “real” UBOs able to control and steer a company are likely to be lost in a flood of notifications to the UBO Register regarding UBOs with mere “rights of prevention”. The result would be less, not more transparency.

Nonetheless, all companies should check what impact the new FAQs could have on how “their” UBOs are determined. The first “wave of checks” after the UBO Register was introduced on 26 June 2017 showed that this may involve a considerable amount of effort, especially for lager groups of companies.

Whether or not a notification to the UBO Register is necessary, or if the notification obligations are deemed to have already been met, or what legal risks exist can only be assessed on the basis of the individual case.

Further points in the FAQs

With regard to further questionable points in the FAQs, the Federal Office is adhering to its view to date.

In multi-level shareholding structures, the obligation to notify the UBO Register may be deemed to have already been met (section 20(2) sentence 1 GwG) where the UBO’s details are already evident from a comprehensive overall review of the various documents and registrations listed in section 22(1) GwG, accessible electronically in the registers specified in section 20(2) sentence 1 GwG. But the Federal Office continues to assume that – of all things – entries in the UBO Register of another entity, e.g. the parent entity, are not sufficient in this regard, even though UBO Register entries are explicitly referred to in section 22(1) sentence 1 no. 1 GwG (FAQs B.IV.1).

The Federal Office also adheres to its view that the notification obligations cannot be deemed to have already been met in regard to a limited partnership where, in addition to the general partners, the limited partners are UBOs as well (FAQs C.II.1, and C.II.2 on exceptions).

Since 1 January 2020, moreover, section 20(3a) GwG requires entities subject to notification obligations to request UBO information from their shareholders in a reasonable scope in case they did not receive such information from their UBOs. The requests for UBO information and answers have to be documented; failure to document them can be punished by a fine (FAQs B.I.4).