Telemedical treatments have become an integral part of the German healthcare system. However, the regulatory framework is complex and subject to constant changes to reflect advances in medicine and healthcare policy. The controversial introduction of the electronic patient record (elektronische Patientenakte, ePA) and e-prescriptions for drugs and digital health applications have further expanded telemedical treatment options. Drug ordering platforms’ cooperation with physicians and pharmacies helps connect and streamline treatment and prescription processes and offers interesting options for strategic investors.

It is important that the legislature strike the right balance between promoting telemedical treatment options and protecting the existing care infrastructure provided by medical practices and pharmacies. For this reason, telemedicine is subject to strict compliance requirements, which have resulted in a number of court rulings in the recent past.

In the following, our experts Enno Burk and Christoph Schoppe give you a practical overview of the current legal framework for telemedicine in Germany, highlighting the challenges that arise from the rapid growth of digital treatment options alongside different healthcare policy priorities.

We hope you find this article insightful and interesting. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions.

I. Online consultations to become the norm: New requirements for SHI-accredited physicians

Remote-only treatment has been legally permissible since 2018 – on the condition that it is medically justifiable and is carried out with the necessary care (section 7(4) Model Professional Code for Physicians in Germany (Musterberufsordnung für die in Deutschland tätigen Ärztinnen und Ärzte), which has in the meantime been adopted by all state medical associations).

This development is now better reflected in the Federal Framework Contract pertaining to Physicians (Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte, “BMV-Ä”) negotiated between the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds: As a result of the new Annex 31c to the BMV-Ä of 1 March 2025, online consultations will become the norm for SHI-accredited physicians. All SHI-accredited physicians are to offer video consultations where medically appropriate and organisationally feasible (section 6(1) Annex 31c BMV-Ä). However, the minimum number of consultation hours on site in the practice will not change (section 9(1) Annex 31c BMV-Ä).

In addition, the new annex to the BMV-Ä specifies the requirements governing patient access to video consultations. Access must be simple and barrier-free. Online consultations must be scheduled in a non-discriminatory manner. Patients are to be prioritised solely according to their need for medical treatment (section 6(2) Annex 31c BMV-Ä).

As of 1 September 2025, patients living in close proximity to the practice must also be given priority when appointments are scheduled (section 7(1) Annex 31c BMV-Ä). This seems surprising at first, given that one of the advantages of video consultations is that long journeys can be avoided. However, the policy is actually intended to facilitate structured follow-up care in the event that further treatment is required. Exceptions will remain permissible (section 7(3) and (4) Annex 31c BMV-Ä).

Annex 31 also specifies new technical and spatial requirements for remote workspaces. Even though section 24(8) Ordinance on the Accreditation of SHI-Physicians (Zulassungsverordnung für Vertragsärzte, “Ärzte-ZV”) now allows online consultations to be held outside the practice premises, certain conditions still have to be met. Section 8(1) Annex 31c BMV-Ä refers to the following requirements in particular:

- A dedicated, enclosed space

- Availability by telephone during normal practice opening hours

- Access to, and ability to make full use of, the electronic patient record and the telematics infrastructure applications in accordance with section 334 Social Security Code, Book V (Sozialgesetzbuch, Fünftes Buch, “SGB V”)

Important: The remote workspace must be located within Germany (section 8(3)). SHI-accredited physicians are therefore not allowed to work remotely from abroad (e.g. working while on holiday).

However, SHI-accredited physicians must continue to fulfil their existing duties to offer minimum consultation hours and open consultation hours at the SHI-registered office (section 24(8) Ärzte-ZV). Purely online SHI-accredited practices do not exist at present, nor are there any plans to introduce such practices. The SHI-accredited physician’s work will continue to be focussed on patient care on site, in the physician’s practice.

II. Minimum technical requirements for telemedical products

Entry into the market of telemedicine as a video consultation provider is contingent on compliance with specific technical requirements:

- Video service providers who facilitate video consultations as well as communication service providers who transmit data for physicians to confer on findings must be certified in accordance with the requirements of Annex 31a and 31b BMV-Ä. Among other things, they must comply with data protection and data security requirements.

- Compliance with the requirements imposed by the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-Spitzenverband) and the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is verified by independent certifying bodies which check the relevant proof that must be provided. Currently, there are 88 certified video service providers (as of 13 May 2025). This number more than doubled in less than a year (43 certified video service providers in September 2024).

III. Will there be competition between the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians and private telemedicine portals?

- Section 370a(1) SGB V provides that the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is to set up – for SHI patients – a new electronic system for assigning online consultation hours with SHI-accredited physicians. The Digital Act (Digital-Gesetz, “DigiG”) has introduced deadlines for this purpose: 30 June 2024 for the referral of telemedical services and 30 June 2025 for the referral of in-person appointments. Both video consultations and in-person appointments can now be booked online via the 116117 patient service, for which the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is responsible (116117.de - Der Patientenservice: die Leistungen | 116117.de).

- The private portals already established in the market must pay a fee to receive the information provided in the electronic portal of the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians (section 370a(4), sentence 1 SGB V).

- The Federal Government is also actively involved in digital health information. In existence since 2020, the national health portal https://gesund.bund.de/en provides information on health and nursing care in clear, easily understandable language, is available to people with disabilities, and can be accessed via both the internet and the telematics infrastructure (section 395(1) SGB V).

IV. Advertising of telemedical treatment

By way of exception to the general ban on advertising remote treatment set out in section 9, sentence 1 Health Products and Services Advertising Act (Heilmittelwerbegesetz, “HWG”), telemedical treatment can be advertised where generally recognised professional standards do not dictate that physician and patient meet in person (section 9, sentence 2 HWG). Higher regional courts initially applied an unnecessarily narrow interpretation of this new provision (see for example Munich Higher Regional Court, judgment of 9 July 2020 – 6 U 5180/19; Hamburg Higher Regional Court, judgment of 5 November 2020 – 5 U 175/19).

In its judgment of 9 December 2021 (I ZR 146/20), the Federal Court of Justice defined the criteria for “generally recognised professional standards”, setting Germany’s first standard for what remote treatments – a category that includes video consultations – can be advertised in accordance with the requirements of section 9, sentence 2 HWG:

- To ensure a consistent, legally sound application of section 9, sentence 2 HWG, the interpretation of the “generally recognised professional standards” must draw on the identical term in section 630a(2) Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, “BGB”) as well as the principles developed with regard to this term and a physician’s duties under their medical treatment contract with the patient (Behandlungsvertrag). The upside is that such interpretation can draw on extensive case law, enabling consistent, legally sound application of section 9, sentence 2 HWG.

- By contrast, section 9 HWG does not depend on whether the advertised remote treatment would be permissible under Germany’s medical professional laws.

The Federal Court of Justice pointed to the continuing exceptional nature of remote treatments while acknowledging that legislators wanted to further develop telemedicine services, making clear that as long as professional standards were complied with, it would not oppose such developments.

However, current case law shows that a strict standard must still be applied:

- Frankfurt Higher Regional Court recently clarified that remote treatment cannot be advertised as face-to-face medicine (judgment of 6 March 2025 – 6 U 74/24). Patients must be able to recognise that remote treatment has limitations and is not suitable for every indication.

- Munich I Regional Court rejected the prescription of obesity medication based solely on questionnaires (judgment of 3 March 2025 – 4 HK O 15458/24). The medical standard calls for more comprehensive testing, it said.

- Cologne Higher Regional Court found that more than digital forms were needed to treat asthma and erectile disfunction (judgment of 10 June 2022 – I-6 U 204/21): The lack of non-verbal impressions and inability to ask follow-up questions made proper remote treatment impossible, it said.

V. Advertising of prescription drugs

Section 10 HWG prohibits the advertising of prescription drugs to the public. Recent court decisions demonstrate this provision’s relevance to numerous telemedicine platforms: In the aforementioned decision (Frankfurt Higher Regional Court, judgment of 6 March 2025 – 6 U 74/24), Frankfurt Higher Regional Court ruled that even specifying a medicinal product by name on a website (e.g. medical cannabis) violates the prohibition in section 10 HWG if its specification is intended to promote sales.

Indirect advertising – for example, establishing a connection between a diagnosis and the offer of a specific medication – may also fall under this prohibition. This was also established by Munich I Regional Court in the aforementioned judgment of 3 March 2025 – 4 HK O 15458/24, in which reference was made only to a “weight loss treatment”, but the context created clear association with the specific drug that was being promoted.

Platforms must therefore make a careful distinction between pure information and advertising. General information about illnesses is permissible, but specific recommendations on prescription drugs are not – and the boundaries are fluid. The mere mention or visual depiction of a medicinal product may be sufficient to constitute impermissible advertising within the meaning of section 10 HWG. Because it always comes down to the specific way the information is presented on the website, we recommend full legal review prior to launch to prevent violations and the consequences that may follow.

VI. Pharmacy law hurdles: Caution required when forwarding prescriptions to partner pharmacies

Telemedical platforms often cooperate with (mail-order) pharmacies to give their customers an immediate source of supply for any prescribed medicines. But caution is advised: Pharmacy law demands neutrality in the choice of dispensary. Section 11(1a) Pharmacy Act (Apothekengesetz, “ApoG”) prohibits the collection and forwarding of prescriptions in exchange for payment or other benefit. Patients’ freedom to choose a pharmacy must also always be respected.

The Federal Court of Justice has clarified that online marketplaces that list (partner) pharmacies in exchange for a flat fee do not automatically violate the ban (judgment of 20 February 2025 – I ZR 46/24). Specifically, the Federal Court of Justice ruled that section 11(1a) ApoG requires a direct connection between the benefit granted and the actions specified in that section; the payment would thus have to be made specifically for forwarding or brokering prescriptions to run afoul of the ban. That didn’t apply to a monthly flat fee paid regardless of the number of medicinal product sold via the platform, it said.

In addition, telemedical platforms must not restrict the freedom to choose a pharmacy. The Federal Court of Justice did not consider this freedom to have been restricted in the specific case. While the platform only showed pharmacies that had concluded a partnership contract, that did not restrict the customer’s freedom of choice, because the decision to use the platform was merely an expression of their right to choose, it said.

For a comprehensive look at the Federal Court of Justice’s decision, see our article of 11 March 2025 (Federal Court of Justice Rules on Pharmacy Marketplaces: Green Light for Digital Distribution Models (BGH I ZR 46/24) | Gleiss Lutz).

VII. Medical device law hurdles

If telemedical treatment involves the use of wearables or networked diagnostics devices, such devices generally fall under the EU Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) where they fulfil functions with an intended medical purpose. According to Annex VIII Rule 11MDR, software used for diagnosis or monitoring must be assigned to at least risk class IIa (see, for example Hanseatic Higher Regional Court, judgment of 20 June 2024 – 3 U 3/24 regarding a dermatological diagnostics app).

VIII. Boosting demand for telemedicine services

Introducing video consultation, the volume of which is no longer restricted by law, enables physicians to render telemedicine services from home and be remunerated for them. Germany’s digitalisation of its healthcare system also includes a number of further projects to improve both information for physicians as well as prescribable treatment from the patient’s perspective. Better integration allows for a broader spectrum of services than before. The following measures are noteworthy:

1. The electronic patient record (ePA)

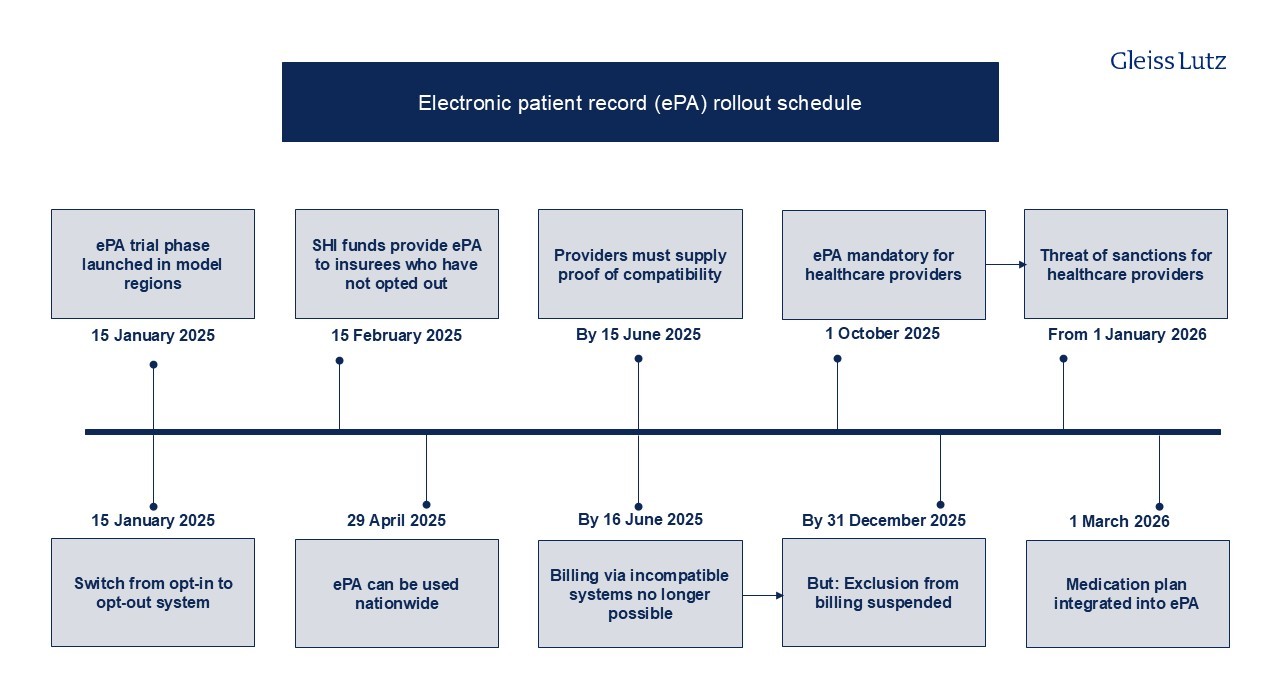

The electronic patient record constitutes a core element of digital networked healthcare and the telematics infrastructure. Since 2021, all SHI funds have been obliged to offer electronic patient records to their members and all physicians and psychotherapists required to have the necessary equipment to transmit data to the patients’ central electronic patient record via the telematics infrastructure. Digital patient data are collected in one central location. The rollout for electronic patient record rollout timetable is currently as follows:

2. Introduction of e-prescriptions across Germany

- The obligatory use of e-prescriptions – which were already introduced in 2022 – across Germany was long delayed on account of technical requirements and data protection concerns. Since 1 January 2024, the e-prescriptions have become the binding standard for supplying SHI patients with medicinal products.

- Physicians issue an e-prescription digitally, signing it electronically with their health professional card. It is then stored and encrypted in the telematics infrastructure, where pharmacies can access it later. On the technical side, practices need an electronic health professional card, a link to the telematics infrastructure with a corresponding connector, and a practice management system that meets e-prescription requirements.

- Patients receive an access code (token) that they then give the pharmacy for the prescription to be filled.

- There are various ways of sending the token to the patients and of having the prescription filled by the pharmacy:

- Via e-prescription app

- Printing out the token and having it scanned in the pharmacy

- Having the e-prescription filled using the electronic health card, which needs to be inserted into a reader at the pharmacy.

- CardLink procedure: Prescription is filled using the electronic health card and a smartphone without having to physically insert the card into a card reader (NFC solution)

- Since 2024, all private health insurance companies and SHI funds have been able to include a function in their electronic patient record apps enabling e-prescriptions to be received and filled.

- Further development of the e-prescription based on the DigiG by integrating it into the electronic patient record: Integration goes beyond merely showing an e-prescription on the app’s user interface. Unless the patient objects, further data will be sent to the electronic patient record, including drugs dispensed, batch number, and dosage (“dispenser information”).

- Data transfer forms one of the pillars of a digitally supported medication process. Together with further information on allergies, intolerances, pregnancies etc., the data are made available to practices and taken into account when prescribing drugs. The combination of e-prescriptions and electronic patient records makes therapy much more effective. It helps prevent duplicate prescriptions and improves patient safety by allowing physicians to more accurately assess potential drug interactions or conflicts with existing conditions.

- Currently, e-prescriptions only cover prescription drugs and, since the beginning of 2025, digital health applications (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen, “DiGAs”), but they will likely cover all medicinal products in future.

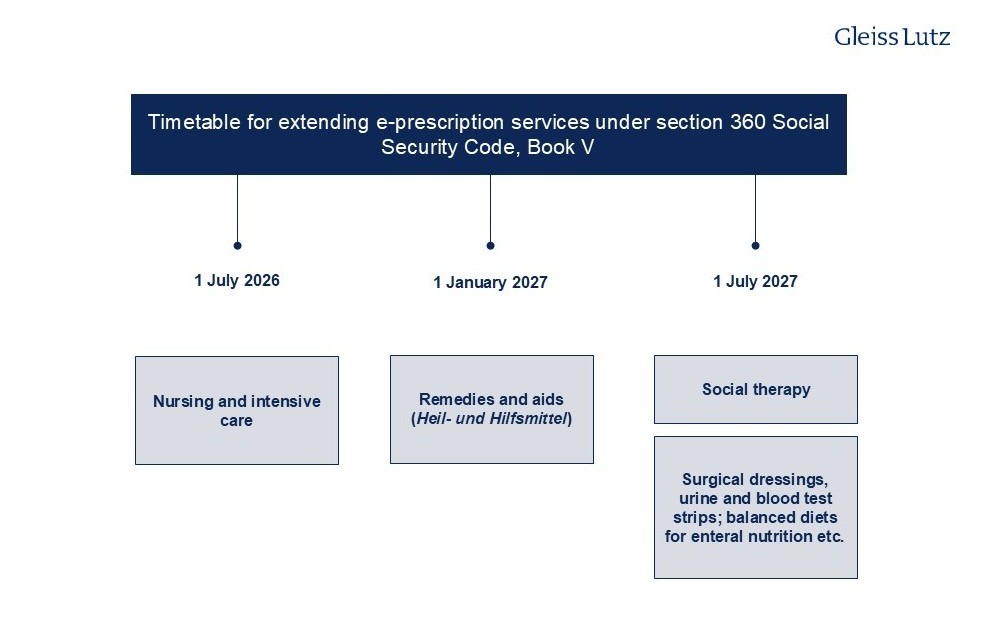

- The following overview shows the schedule for extending e-prescriptions to other services:

3. Digital health apps and telemedicine

- Since the Digital Healthcare Act (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz, “DVG”) was enacted in 2020, digital health applications have been a recognised service within the statutory health insurance system. This has fostered the growth of a new and innovative industry for digital medical device manufacturers.

- 57 apps are currently provisionally or permanently listed in the official digital health applications directory of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, “BfArM”). Twelve applications (provisionally) authorised as digital health apps have been removed from the list either at the request of the developer or because no positive effect on healthcare provision (positiver Versorgungseffekt) could be demonstrated.

- Before the DigiG came into force, only class I or IIa medical devices whose main function is based on digital technologies could be prescribed as digital health apps. The DigiG has extended the statutory entitlement to include apps falling under higher risk classes, namely those in risk class IIb. This means that it will be possible to use digital health apps in more complex therapeutic processes as well, for remote patient monitoring for example. This opens up new opportunities for digital health app developers.

- Before they become prescribable in statutory health insurance, digital health apps must be included in the directory of digital health applications by the BfArM pursuant to section 139e SGB V. The areas of application of the digital health apps listed range from treating depression to diabetes and multiple sclerosis through to migraines. According to the DiGA report of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds from 2024, over 1 million DiGAs were prescribed between 2020 and 31 December 2024.

- The DigiG has changed the way digital health apps are priced, with performance-based criteria playing a greater role. Section 134(1), sentence 3 SGB V stipulates that as from 1 January 2026, agreements must specify that performance-based price components are to comprise at least 20 percent of remuneration.

- The DigiG also treats digital health apps the same as any other remedies and aids offered to pregnant women and new mothers, which means that women now have the right to use relevant digital health apps both during and after pregnancy (section 24e, sentence 1 SGB V).

- The performance of all digital health apps listed in the directory must now be assessed and the results reported to the BfArM on an ongoing basis. The results are also to be published in the directory from 1 January 2026 onwards. As already set out, part of a digital health app developer’s remuneration will depend on these results.

4. Opportunities to invest in digital health

- Public healthcare entities also have the opportunity to invest in digital health. Such entities include SHI funds, regional associations of SHI-accredited physicians, the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians and the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Dentists (Kassenzahnärztliche Bundesvereinigung). Pursuant to section 68a et seq. SGB V, these are entitled to promote digital innovations by assuming some or all of the costs. Digital innovations include telemedicine/networked healthcare and digital medical devices.

- SHI funds may also support or commission development by external providers. Now that the DigiG has come into force, SHI funds may invest up to 10% – instead of the previous 2% – of their financial reserves as venture capital for developing digital innovations (section 263a SGB V).

- In the development and shaping of digital healthcare, this gives SHI funds and regional associations of SHI-accredited physicians considerably more scope for cooperation with both established providers and start-ups in telemedicine services and digital medical devices.

IX. Breaking new ground moment in telemedicine

Germany’s telemedical care infrastructure has seen substantial improvements and expansion in recent years. Previous statutory restrictions on the percentage of video consultations have been lifted, giving – once the German medical profession’s self-governing bodies have implemented the DigiG – SHI-accredited physicians greater flexibility and scope in offering such consultations, especially combined with the now permitted option of working from home.

Developments in e-prescriptions and the electronic patient record are simplifying how prescriptions are issued, sent and filled in everyday practice. Online pharmacies and pharmacy platforms are also likely to benefit, as will logistics service providers that offer prompt delivery to patients directly on pharmacies’ behalf.

Digital offerings, however, continue to operate in a complex legal environment where legislators are attempting to strike a balance between promoting digital care options and maintaining existing care infrastructure provided by medical practices and pharmacies. Striking that balance between healthcare policy priorities will remain a challenge in Germany’s future efforts to digitise its healthcare system.